You can find the original post here. This version has been formatted to fit your scr-- I mean, formatted for GameDev.net

.

In 2009 engineers from the University of Wisconsin released a piece of software called PEAT. This software has been used in medicine since as a tool to diagnose patients with photosensitive epilepsy. This is a disease where strobing lights cause seizures, and it currently has no cure. Things that trigger it include lightning, flashing sirens, flickering lights, and other similar strobe effects. Other triggers that seem unrelated, but are also very cyclic in nature, include rapidly changing images, and even certain stationary stripes and checkerboard patterns. This particular form of epilepsy affects roughly 1 in every 10,000 people, and around 3.5 million people worldwide.

.

Despite this number, however, sufferers have to take precautions on their own. Nearly every movie has lightning in it, or camera flashes, and videos online are often a lot worse. With the exception of UK television broadcasts (which are regulated), there are no real preventative measures to combat epileptic events.

.

The next little mini-series of posts talks about my development of a sort of real-time epilepsy protector: a program that watches the current output of a computer monitor and detects when epileptic events may be possible and then blocks the offending region of screen from further flashing. During development, all suggestions are very welcome, as I'm probably going to go about everything in the exact wrong way.

.

Without further ado, let's jump right in.

.

W3C definition

.

The W3C spec for Web Accessibility is the spec that PEAT is implemented from. It defines two types of ways that an epileptic event can occur: general flashes and red flashes. For the rest of this post I'll only be dealing with general flashes, as I want to get the general case out of the way first.

.

So the actual spec is kinda confusing. It mixes units, defines thresholds for passing instead of failing, and tries to mix approximations and measurements. I'm going to take creative liberties to fix these issues and add new terms for further clarity and without loss of meaning of the actual spec.

.

Taking it all apart and extracting the actual meaning, an epileptic event can be triggered when:

- There are more than 3 "general flashes" in a 1 second interval

A general flash is defined as:

- 25% of the pixels in a 0.024 steradian area on the screen, relative to the viewer, all experience the same "frame flash" at the same time

A frame flash is defined per pixel as what happens when:

- There is a decrease followed by an increase, or an increase followed by a decrease in the histogram of luminance for a single pixel. Each increase and decrease satisfy the following:

- The minimum luminance in the histogram over the time-span of the increase or decrease is less than 0.8

- The amount of increase or decrease of luminance in the histogram must be at least 10% of the maximum luminance in the "range" of the increase or decrease

So an epileptic event can be triggered when many pixels agree that a flash happened at the same time. The W3C spec says "concurrently," so I'm taking that to mean "the same frame," even though differing by 1 frame probably isn't discernable to the eye.

.

So you could create a function that takes only a histogram of luminance for a single pixel and be able to get out the frame flashes for that pixel. In fact, all we need to know about the frame flashes of each pixel is when they occur, so that it can be used to determine how many happen concurrently. This is the only thing that is stored about them in the program.

.

There are other details in the W3C spec that I'm ignoring:

- Very "fine" transitions, like 1px x 1px checkerboards alternating colors every frame are fine, because the individual transitions are not discernable to the human eye. This is a complicated one to deal with, for many reasons. However, if you ignore it, you fall prey to detecting flashes in videos of light fog moving, where a lot of the transparency comes from stochastic opacity, or from grain filters. I might address this later.

- It gives some approximations of the areas on the screen you should be looking at for a viewing distance of 22-26 inches with a 15-17 inch screen with resolution 1024x768. This is far too specific to try to generalize to any screen, so I'm going to be doing all the calculations on my own.

I'm also imposing my own restrictions on the definitions above. I have no idea if they're correct, but they make the algorithms more approachable (or rather, it makes the problem less ambiguous)

- The time-span of the increases and decreases of each frame flash cannot overlap between frame flashes in a single pixel

- A general flash is counted if 25% or more of a 0.024 steriadian viewing area experiences a common frame flash. The spec didn't specify, but this is the only thing that makes sense

- I'm only going to be testing fixed areas of 0.024 steradians, instead of trying to find every area that satisfies the conditions in the spec.

So, just as a review of everything, the general pipeline of figuring out if an epileptic event is possible in the past second:

(Sample phase) Create histogram of luminance over the past second of every sampled pixel on the screen(Frame Flash phase) For every pixel: Create a list of all frame flashes by looking at the peaks of their histogram(Gather phase) For each frame: Try to find a 0.024 steradian area where 25% or more pixels experienced a frame flash on that frame If such an area is found, increment the general flash counter by 1If the general flash counter is greater than 3, an epileptic event is possibleSince epileptic events are possible when the general flash counter is greater than 3, protective measures are going to be triggered when the counter is equal to 3. Also, I don't necessarily want to just know if an epileptic event is possible, what I want to do is block it out.

.

In order to break everything up into multiple parts, I'll tackle each stage of the algorithm in order of what needs clarification the most. I'll cover the Frame Flash Detection phase here, and the Sample and Gather phases in another post.

.

Frame Flash Detection

.

So what we need to do is, given a histogram of luminance for a single pixel over the course of 1 second, we need to find every frame that contains a frame flash. However, the big problem is that, most of the time, flashes happen over the course of several frames. So, we need to find a way to not only find the flashes but also associate an entire flash with a single number.

Recall the definition of a frame flash, re-written here:

- There is a decrease followed by an increase, or an increase followed by a decrease in the histogram of luminance for a single pixel. Each increase and decrease satisfy the following:

- The minimum luminance in the histogram over the time-span of the increase or decrease is less than 0.8

- The amount of increase or decrease of luminance in the histogram must be at least 10% of the maximum luminance in the "range" of the increase or decrease

This definition took me 2 or 3 different tries to implement correctly, and I may still be wrong. I blame how cryptic the W3C spec is about this.

.

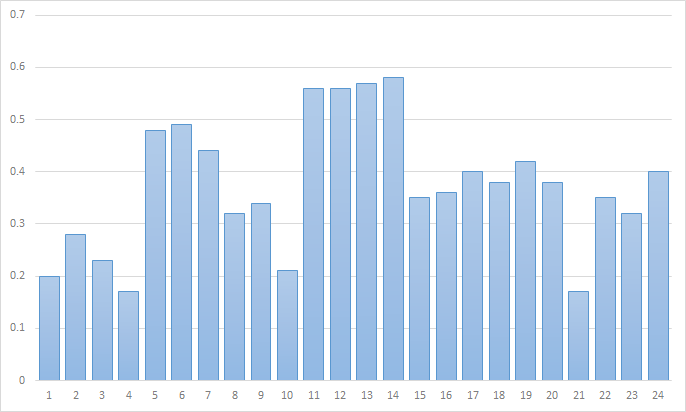

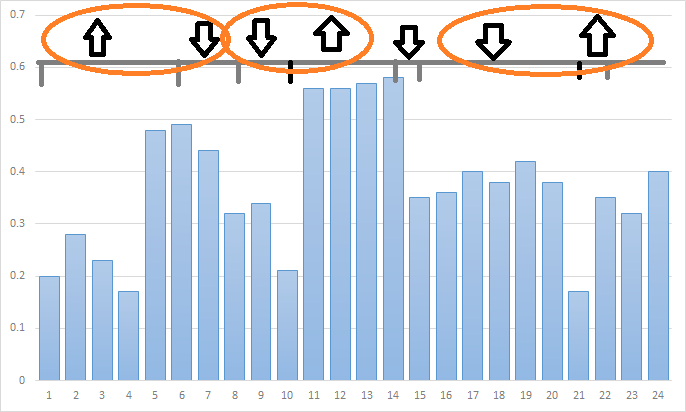

So this is going to be implemented exactly how it's stated. We are going to keep a record of all of the increases and decreases that each satisfy the above constraints, and then match pairs of adjacent increases and decreases. For an example, consider the histogram of luminance:

.

.

In order to find increases and decreases, we're going to look at every local extrema, compare it to the first sample, and see if the difference fulfills the above constraints. If it does, we record the result and now use that sample as the sample to compare future samples against. The code goes something like this:

int extrema[NUM_SAMPLES];transition pairs[NUM_SAMPLES];int numPairs = 0;int lastExtrema = lumHistogram[(sampleCounter + 1) % NUM_SAMPLES];for (int i = 1; i < NUM_SAMPLES - 1; ++i){ int prevI = ...; int currI = ...; int postI = ...; float x_prev = lumHistogram[prevI]; float x_curr = lumHistogram[currI]; float x_post = lumHistogram[postI]; float dx1 = x_curr - x_prev; float dx2 = x_curr - x_post; // test for local extrema if ((dx1 > 0) == (dx2 > 0) && (dx1 != 0) && (dx2 != 0)) { float dx = x_curr - lastExtrema; if (0.1 <= dx && dx <= 0.1) continue; if (lastExtrema > 0.8 && x_curr > 0.8) continue; lastExtrema = x_curr; if (dx1 < 0) pairs[numPairs] = DECREASE; else pairs[numPairs] = INCREASE; extrema[numPairs] = i; ++numPairs; }}.

The extrema[numPairs] = i; part is the part that stores the location of the "frame" of each transition. When it comes time to look for adjacent increases and decreases, you can just pick one of the two "frames" and call that the exact frame of the flash, taking care of that particular problem.

.

Now that we have the frame flashes found, we need to store them in a way that makes it easy on the next stage to use the info, the Gather stage. I'm going to cover that next time, but the general way I'm doing it is by making a giant array of distributions, with each distribution corresponding to a single Gather stage chunk. The specific part of the array is passed to the function so that each sampled pixel can contribute to it. This makes the gather stage really simple.

.

The nice thing about this method of finding frame flashes is that it doesn't matter if you traverse backwards or forwards through the histogram; as long as you're consistent then it'll work well.

.

Conclusion

.

Next time I'll go over how the Gather and Sample stages work. Until then, I'll be continuously working on the project. There are still some to-do's, even with the just the Frame Flash phase. Some of these include:

- Multithreading each sampled pixel, or maybe porting to the GPU. I don't want to port to CUDA because that technology isn't very universal

- Analyzing the pixels adjacent to the current pixel, so as to maybe combat things like grain filters and clouds triggering the detector.

- More stability improvements. The program doesn't pick up on a lot of really obvious cases, especially if they happen in small areas, like epilepsy gifs on Google. I feel like if I could sample at a finer granularity, that problem would go away. This ties back in to multithreading, because reducing the granularity would lead to achieving enough throughput to be able to process that extra granularity.

- For the whole program, minimizing to tray and some other polishing touches. Hopefully these will get resolved in some way or another sometime soon. The current project will be hosted as soon as I'm confident that Nopelepsy v0.1.0 is okay to show the world.

Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for next time!